Aristotelian Ethics: A Gentle Introduction

Every craft and every discipline, and likewise action and decision, seems to seek some good.

“Every craft and every discipline, and likewise action and decision, seems to seek some good."

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 1

Note: The purpose of this piece is not to provide an all-encompassing, complete, detailed, guide on Aristotelian ethics. Rather, it is meant to quickly orient someone with little to no philosophical knowledge to key ideas and concepts related to Aristotle’s Ethics. For those interested in a deeper understanding, explore the references in the “Learn More” section at the bottom of the piece.

Table of Contents

- The Purpose of Aristotelian Ethics

- The Good

- Cultivating Character

- Choices and Deliberation

- Friendship

- Living a Good Life

- Learn More

The Purpose of Aristotelian Ethics

Aristotelian Ethics, often referred to as Aristotle’s Ethics or Virtue Ethics, focuses on the cultivation of a fulfilling, flourishing, and virtuous life. At its core, Aristotelian Ethics seeks to answer one profound question:

"How do I live a good life?"

The foundation of Aristotle’s ethical philosophy is primarily found in his work Nicomachean Ethics. While there are other related texts, some of which remain the subject of historical debate, Nicomachean Ethics stands as the most comprehensive and influential exploration of his ideas on this topic.

In many respects, Nicomachean Ethics can be considered one of the earliest self-help books ever written. It delves into a wide range of themes, from defining what it means to live a good life to examining the importance of friendship in achieving personal fulfillment. Let’s explore some of the core concepts within Aristotle’s seminal work.

The Good

Before we can define what it means to live a good life, we must first understand what is meant by “good” itself. Aristotle defines the "good" as that which a thing aims toward. For example, a cup is considered good if it holds liquid well and maintains the liquid’s temperature. However, if the cup allows a hot liquid to become lukewarm or leaks, it is less "good." This is because the cup’s purpose is to hold liquid effectively and comfortably for its owner.

For humans, our ultimate aim is eudaimonia, often translated as "happiness" or "flourishing." According to Aristotle, anything that contributes to eudaimonia is good. This understanding of the good is teleological, meaning it is rooted in the belief that everything has a purpose (telos, in Greek), and the good is realized when something fulfills its natural function.

Aristotle also highlights a hierarchy of goods. Consider the following example, which illustrates this hierarchy in the context of defending a city:

- Freedom

- Security

- Victory in War

- Victory in Battle

- Cavalry

- Horsemanship

- Riding a Horse

- Bridles

- Bridle Making

At the top of the hierarchy is "freedom," an abstract concept. This freedom is secured through victory in war, which is achieved by cavalry skilled in horsemanship, using proper equipment. Even the act of bridle making, while seemingly mundane, is good because it contributes to the achievement of the higher goods in the hierarchy.

In our everyday lives, we often find ourselves engaged in small tasks that feel tedious or burdensome. However, maintaining an awareness of the hierarchy of goods can lend meaning to these tasks. For example, taking your children to school may seem like a chore, but when viewed in the context of helping them learn and grow to contribute to a better world, it takes on greater significance.

The ability to speak (logos, in Greek) plays a crucial role in our understanding of the good. Through speech, we can discuss abstract concepts, like the "goodness" of a cup. We can conceptualize the ultimate cup, defining its purpose and functions, and judge material objects against abstract ideas. Speech allows us to deliberate on what is good, bad, better, worse, just and unjust, giving us the unique, human capacity to understand the good in ways that other animals cannot.

Cultivating Character

We began with the question, "How do I live a good life?" To answer this, we must pursue eudaimonia. It’s important to note that eudaimonia is not the same as pleasure (hedone, in Greek). While pleasure is fleeting and shallow, such as enjoying a delicious meal, watching a movie, or playing a pickup game of basketball, eudaimonia refers to a deeper, long-term sense of satisfaction. It’s the fulfillment you feel when watching your family interact during the holidays and taking pride in the way you’ve raised your children. It’s the sense of accomplishment that comes from seeing years of hard work and dedication finally come to fruition.

So, how does one pursue eudaimonia? Aristotle suggests that the cultivation of one’s character is key. The word character itself comes from the Greek term χαρακτήρ (charaktēr), which means "engraving tool" or "mark." This connection to etching is both literal and metaphorical, reflecting how traits and qualities are deeply "impressed" or "engraved" into us through habit and experience.

To cultivate our character, we must make choices that align with the pursuit of virtues. It is through consistent, repeated choices over time that we develop the character necessary for eudaimonia.

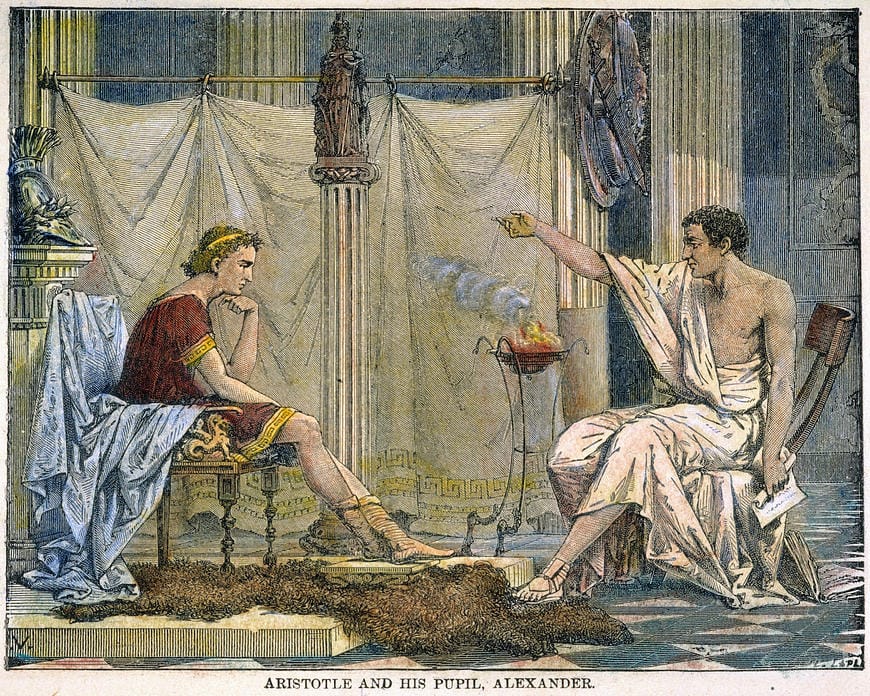

By Charles Laplante, "That most enduring of romantic images, Aristotle tutoring the future conqueror Alexander.", 1866

Virtues are positive character traits that enable us to act in ways that align with moral excellence and promote flourishing. Aristotle divides virtues into two categories: moral virtues and intellectual virtues. Courage, truthfulness, patience, justice, and wisdom are all examples of virtues. Each virtue exists in a balance between excess and deficiency. For example, too much courage can lead to recklessness, while too little can result in cowardice. It is through rational thought and deliberation that we find the right balance in each decision we make.

In short, we can achieve eudaimonia by cultivating our character. This is done by using our rationality to pursue virtues in our everyday actions.

Choices and Deliberation

A key aspect of cultivating character is the act of deliberating and making choices. The choices we make shape who we are, so making the right choices is crucial. As discussed earlier, we aim to find balance between excess and deficiency within each virtue. For example, we seek to be courageous, but not cowardly or reckless; generous, but not wasteful or stingy; witty, but not boorish or foolish.

Aristotle also notes that moral virtue involves not only choosing the right action but doing so in the right way, at the right time, and in the right amount. Virtue lies in the balance between deficiency and excess, what he calls the "golden mean." Making the right choices requires practical wisdom. However, Aristotle points out that there is no fixed rule to determine this balance; instead, we must rely on trial and error. Through experience, we learn to identify what constitutes the correct balance between excess and deficiency.

To make these right choices, Aristotle tells us we must deliberate. In Nicomachean Ethics, deliberation is a very specific concept, it concerns things that are within our control. For instance, we don’t deliberate about how we could be a foot and a half taller, because that is beyond our control. Instead, we deliberate over things like how to help a friend struggling with addiction, how to solve a problem at work, or whether to accept a promotion.

While Aristotle emphasizes the importance of rationality in deliberation, he also advises us to heed our inner voice. He suggests that, deep down, we often have an intuitive sense of what is right and wrong. Rather than disregarding our feelings and inclinations, we should acknowledge them and let them serve as a subtle guide, working alongside rational thought to inform our actions.

Deliberation is goal-directed and focuses on the means to achieve a particular end. Aristotle distinguishes between ends (final goals) and means (the actions or methods to achieve those goals). For example, if the goal is to live a virtuous life, deliberation is concerned with deciding the appropriate actions and habits that will cultivate virtues. It does not focus on whether we should live a virtuous life (the end), but on how to act virtuously (the means).

Choice, then, is the decision to act based on one’s rational deliberation. It is voluntary and guided by reasoning. A virtuous person, according to Aristotle, makes choices that align with their rational understanding of what is good. Ultimately, we deliberate over things within our control, make the best choice, and act on it. If we consistently do this in pursuit of virtues and strike the right balance, we will cultivate a strong character.

Friendship

Aristotle devotes a significant portion of Nicomachean Ethics to friendship, describing it as a cornerstone of a flourishing life and a reflection of moral character and virtue. He categorizes friendship into three types: friendships of utility, friendships of pleasure, and friendships of virtue.

Friendships of utility are based on mutual benefit or practicality. These relationships, such as those with a local merchant or coworker, exist because both parties gain something from the connection. While they may involve goodwill and politeness, they tend to dissolve when the utility no longer exists.

Friendships of pleasure arise from the enjoyment individuals find in each other's company. These friendships are often formed around shared hobbies, activities, or entertainment. They involve joking, camaraderie, and shared experiences. However, like friendships of utility, they are typically short-lived and fade when the source of pleasure is no longer present.

Friendships of virtue, according to Aristotle, represent the highest form of friendship. These are built on mutual respect and admiration for each other's character and virtue. In such relationships, individuals wish the best for one another not because of external benefits like usefulness or pleasure, but for the intrinsic good of the other person. These friendships often develop between those who actively pursue virtue together, with each acting as a "mirror" that reflects and refines the other’s character. Friendships of virtue are rare and require both individuals to be truly virtuous and committed to seeking the good.

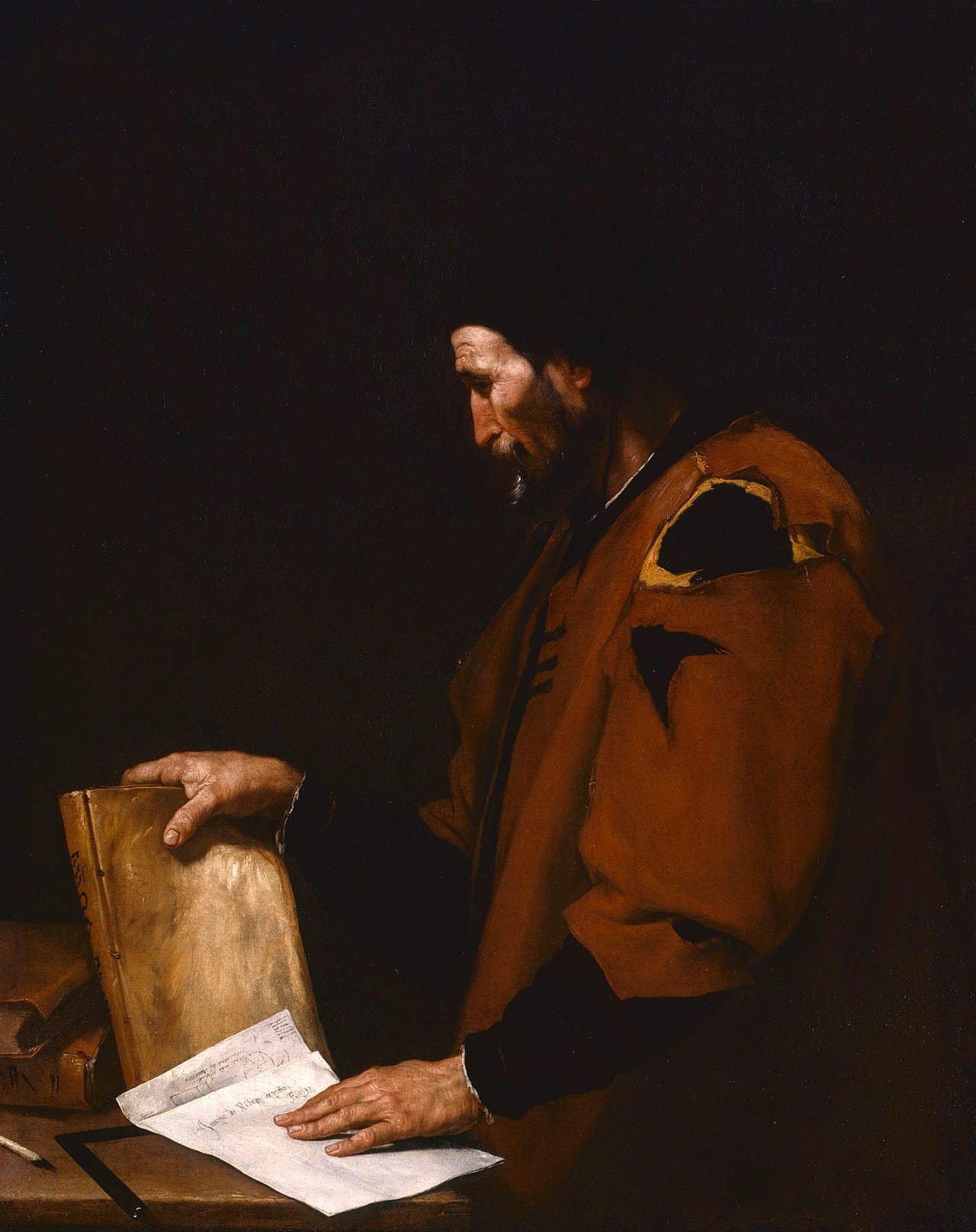

Aristotle by Jusepe de Ribera. Oil on canvas, 1637

Aristotle emphasizes that all types of friendship are essential to living a virtuous and fulfilling life. Humans are inherently social beings, and friendship plays a critical role in our happiness. Furthermore, friendships strengthen communities by fostering trust, reducing resentment, and creating bonds that promote collective pursuit of virtue and well-being.

Lastly, Aristotle claims that true friendship is rooted in self-love, but not in a selfish sense. Instead, it means valuing oneself as a virtuous and worthy person. Only someone who loves and respects themselves can form deep, meaningful friendships with others. Self-love in this context involves pursuing one’s own flourishing and, by extension, supporting the flourishing of one’s friends.

Living a Good Life

We began with a simple yet profound question:

"How do I live a good life?"

Aristotle’s ethics offers a thoughtful answer: we live a good life by pursuing the “good.” For humans, the good aligns with our natural purpose, which is to achieve happiness, flourishing, and eudaimonia. To fill our lives with these deeper, enduring feelings, we must cultivate our character.

This cultivation happens through deliberate choices, decisions that align with virtues. These choices should avoid extremes, seeking instead the right balance between excess and deficiency. By consistently making virtuous choices, we gradually shape a moral and virtuous character. Over time, this character forms the foundation of a truly fulfilling and meaningful life.

Human existence is one of both tragedy and beauty. We are brought into the world through no choice of our own, burdened by an inescapable finitude. In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle acknowledges these limitations and offers a framework for making the most of our brief time. His advice is simple, timeless, and applicable to nearly everyone.