The Pitfalls of Naive Empiricism

If a blind man were to ask me if I have two hands, why would I check with my eyes?

“If a blind man were to ask me if I have two hands, why would I check with my eyes?"

— Ludwig Wittgenstein, On Certainty (paraphrased)

Table of Contents

- Diagnosing the Problem

- The Seduction of Precision

- Wittgenstein’s Ruler and Gathering Information

- Applying the Ruler

- Naive Empiricism

- Don't Be A Sucker

Diagnosing The Problem

You arrive for your annual physical on a quiet, weekday morning. The clinic smells of disinfectant and stale coffee. You sign in, flip through a magazine, and wait with mild impatience. Your life is steady, routine, boring. You possess a good job, manageable stress and a family that loves you. There’s no reason to expect anything unusual.

The exam unfolds exactly as it always does: the stethoscope cool against your skin, the doctor asking simple questions about work, sleep, and your spouse while blood is drawn. Fifteen minutes later, you’re back in your car, the appointment already fading from memory.

Three days later, an unfamiliar number lights up your phone. The nurse’s voice is terse and firm as she asks you to come in immediately, offering no explanation. You cancel a meeting and tell yourself it’s probably nothing, yet your chest feels heavy with worry as you grab your car keys.

The exam room looks the same, but it feels smaller this time, more constricting. The doctor enters abruptly, her usual smile replaced by a flat, dry expression. She gets straight to the point.

“I’m sorry,” she says factually, “The blood work is conclusive. You have a rare, life-threatening disease. There is no cure. You have about a month to live.”

She continues speaking, but your hearing is muffled by a faint ringing. It sounds as if you’re floating underwater. You nod blankly as she slides a pamphlet across the desk, barely registering her message.

In the parking lot, the world feels surreal. You sit in your car, watching people come and go from the clinic, oblivious to your situation. Your phone rings sharply, pulling you back to reality. Your wedding photo fills the screen, your spouse’s smile beaming back at you. Your throat tightens as you lift the phone to your ear, searching for the courage to deliver the bad news.

The Seduction of Precision

Unfortunately, the scenario above is not uncommon. Fortunately, if the scenario above did happen, you may not have the rare, life-threatening disease.

Mishaps with diagnostic tests happen. A woman sued a medical center in 2017 because she had her breasts and uterus removed after a diagnostic test incorrectly indicated that she was genetically predisposed to aggressive breast and ovarian cancers. It is common in the medical field for practitioners to overestimate test results.

This issue isn’t confined to medicine. Almost all of us use some tool or medium to “measure” our reality every day. When a result appears precise, quantified, labeled and stamped with authority, it is often taken as evidence of its own reliability. We ask what the measurement tells us, but rarely how it was taken. The act of measurement is mistaken for a guarantee of accuracy, and the possibility that the measurement itself might be misleading is ignored.

Who doesn’t love precision? We have a bias towards precise numbers. In his book Trust in Numbers, historian of science Theodore Porter argues that quantification functions less as a pathway to truth than as a substitute for trust. Numbers gain authority precisely because they appear impersonal, rule-bound, and independent of human judgment. In contexts where expertise is contested or accountability is demanded, numerical representations provide credibility by minimizing the visibility of discretion and interpretation.

Just because measurement and quantification feels more accurate, doesn’t mean that it is. Feeling more accurate is not the same as being accurate. A clearer understanding of information and measurement begins not with the conclusions we draw, but with the methods used to produce them. Let’s talk about Wittgenstein’s Ruler.

Wittgenstein's Ruler and Gathering Information

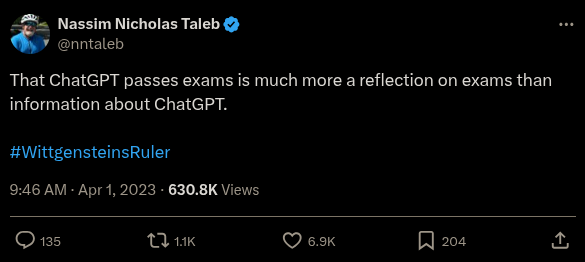

Wittgenstein’s Ruler states that “unless you have confidence in the ruler’s reliability, if you use a ruler to measure a table you may also be using the table to measure the ruler.” It is a concept originally from Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness, that builds on Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy of measurement and uncertainty.

“Unless the source of a statement has extremely high qualifications, the statement will be more revealing of the author than the information intended by him. This applies to matters of judgment. According to Wittgenstein’s ruler: Unless you have confidence in the ruler’s reliability, if you use a ruler to measure a table you may also be using the table to measure the ruler. The less you trust the ruler’s reliability, the more information you are getting about the ruler and the less about the table."

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled by Randomness

Put simply: If your instrument of measurement (whether a tool, a model, or even a person) is unreliable or uncertain, you can’t trust what it tells you about the thing being measured. Instead, what you learn might be more about the measuring instrument itself than the thing it’s supposed to measure.

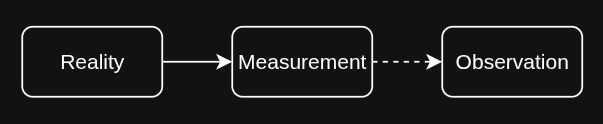

You can break our information gathering process into three key concepts:

- Reality

- Measurement

- Observation

Our observations about the world are shaped by the world itself, but also the way that we take in information. It is impossible to separate the two.

Reality is what happens independent of our observation. It is matter, physics, molecules and chemistry. It is the collection of things that make up our world even if we aren’t observing them.

Measurement is the way we understand our reality. It could be our eyes, the nightly news, a yardstick, or a podcast. We never truly observe reality, rather, it is mediated through something. Measurement constitutes anything that conveys information about reality, but is not reality itself.

Observation is the conclusion we come to. It is the opinion that the chair in front of you is blue, that your couch is over three feet tall, or the belief that a foreign country is a dangerous place based on the podcast you just finished. Observations are a function of both reality and measurement.

To drive these concepts home, lets walk through a few examples.

Applying the Ruler

The News

Imagine finishing a recent Guardian article on trade tensions between China and the United States. As a reader, What is reality, measurement, and observation?

In this setting, reality consists of the full set of actions taken by both governments. Neither the Chinese nor the U.S. government is a single actor; each is a collection of individuals making decisions within institutions. Reality, then, is the accumulated result of those decisions up to the moment the article went to print.

Measurement is the article itself. It is not a neutral window onto events, but a constructed artifact: words selected, framed, edited, and published by an organization. Reporters, editors, and fact-checkers shape the narrative, choosing which events to emphasize and how to connect them into a coherent story about global trade.

Your observation emerges from reading the piece. You might conclude that tensions are escalating, or worry about the long-term stability of the relationship between the two countries. These beliefs feel like direct insights into the world.

But what are you actually learning? While it may seem that your understanding of geopolitics has improved, you may instead be learning how the Guardian interprets those events. The article communicates not only facts about trade, but also the paper’s editorial priorities, framing choices, and institutional perspective. Without a deep understanding of everything that went into publishing the article, how can you be confident that your observations are accurate?

Statistical Modeling

Consider a scenario in which the Federal Reserve releases an economic forecast predicting inflation, employment levels, and GDP growth over the coming years. Investors react, policymakers debate, and businesses adjust their plans. What is reality, measurement, and observation?

Reality, in this case, is the the economy and it’s future. It is shaped by millions of decentralized choices: households deciding how much to spend, firms choosing whether to hire, banks extending or tightening credit, legislators passing laws, and unforeseen shocks rippling through global markets.

The measurement is the forecasting model itself. Built from historical data and economic theory, the model encodes judgments about which variables matter, which relationships are stable, and how uncertainty should be represented. Methodological choices, often invisible, strongly influence the forecasting model.

The observation is the forecasted numbers: projected inflation paths, employment rates, growth curves, and ranges of uncertainty. These figures are treated as actionable signals, guiding interest-rate decisions and shaping market expectations.

Yet the question remains, what is being measured? Although the forecast appears to describe the future economy, it also reflects the Federal Reserve’s modeling framework. The projections embed assumptions about risk, theory, and institutional priorities. In practice, the model often reveals as much about how the Fed thinks about the economy, as it does about what will actually happen.

The Scientific Method

Now suppose a scientific paper is published claiming to explain a newly identified dietary effect. Other researchers review the findings, citations accumulate, and clinicians begin adjusting nutritional recommendations. In this case, what is reality, measurement, and observation?

Here, reality is the underlying biological phenomenon the study seeks to explain. It consists of complex physiological and chemical processes operating according to natural laws. This reality exists independently of the experiment and cannot be observed directly.

Measurement is the particular implementation of the scientific method used in the study. Experimental design, measurement tools, sample selection, study duration, and statistical techniques all shape what data is collected and how it is interpreted. These choices constrain what can be detected and what remains invisible.

The observation is the published paper itself. The statistical findings, inferred causal relationships, and summarized conclusions. These outcomes are often treated as reliable representations of nature, prompting doctors, trainers, and clinicians to adjust their practices accordingly.

But again, what is truly being measured? While the study aims to understand dietary effects, it also measures the capabilities and limits of the scientific method. Publication incentives, funding pressures, and prevailing theoretical frameworks influence what gets studied and how results are presented. Science remains one of our most powerful tools for understanding the world, but it is not free of distortion. Its measurements, too, are subjected to distortion and bias in some form.

Naive Empiricism

Should you watch the news? Should you ignore the Fed’s economic forecasts? Should you “trust the science”?

There isn’t a binary answer to these questions. What Wittgenstein’s ruler does, is help us consider and determine to what extent our measurements reveal reality versus measurement itself. It is a tool to hedge naive empiricism.

The Astronomer by Johannes Vermeer, "A pendant painting to 'The Geographer', the feature image of this post, depicts a 17th century astronomer studying the globe.", 1668

Naive empiricism is the belief that observation or sensory experience alone is sufficient to yield reliable knowledge, without recognizing the theory-laden, context-dependent, or interpretive nature of observation. Everything we observe is mediated through something. For example:

- Sensory experience is mediated through the brain, and shaped by heuristics, attention limits, prior beliefs, and perceptual biases.

- Economic indicators like inflation, unemployment and GDP are mediated through definitions, data-collection methods, seasonal adjustments, and statistical models that embed theoretical assumptions.

- Medical diagnoses are mediated through diagnostic tests, reference ranges, and clinical guidelines, each with false positives, false negatives, and institutional incentives.

- Scientific measurements are mediated through instruments, experimental design, and statistical thresholds, which determine what counts as signal and noise.

- Public opinion is mediated through surveys, polling methodologies, question framing, and sampling choices.

- Climate data is mediated through proxies, sensor placement, historical reconstruction methods, and models used to interpolate missing data.

- Legal judgments are mediated through evidentiary rules, procedural constraints, and interpretive frameworks rather than direct access to truth.

- Historical accounts are mediated through surviving documents, translations, author perspectives, and later reinterpretations.

In the 21st century we are awash in data and metrics. It’s virtually impossible to consume news media without at least one statistic supporting a claim. Data makes us feel certain, precise and accurate. It changes opinions into facts, and puts weight behind ideas. Unfortunately, not all data is equal.

All data, all metrics, all statistics are subject to Wittgenstein’s ruler and the processes by which they come to be. Facts, metrics and data alone are not solely sufficient to make claims about reality, less we fall victim to naive empiricism.

Don't Be A Sucker

Data, measurement, numbers and statistics aren’t going anywhere. We are in the throes of the information age, so where does that leave us?

There are three actions you can take to apply Wittgenstein’s ruler, and ensure that you don’t end up measuring your “ruler” instead of reality:

- Before asking “What does the information say?” ask “How was the information collected?”

- Check your need for metrics and certainty

- Develop a bias towards skepticism and abstaining from judgment

We are inundated with information constantly. When presented with something, stop to ask yourself how the information was collected first. Ignore the conclusion, and focus on the process. Identify how reliable and repeatable it actually is. Explicitly state, or write down the biases introduced by the process used to gather information. Only when you are truly confident that the information is gathered in an epistemically sound way, should you reveal the conclusion.

Second, consider if measurement, metrics and certainty are truly necessary. Do you really need statistics about BMI for your age group to begin your workout routine? Is it valuable for you to consume news about regional conflicts in Africa? Do you need to rely on the Federal Reserve’s economic forecasts to successfully invest your capital, or is there a way to hedge the turbulent economy without this information?

In all the above cases you are pursuing knowledge that is mediated through a “ruler”. Start by determining the purpose of seeking knowledge. Is there a key decision you are trying to make? Would you make a different decision if presented with new information? If the answer is no, avoid pursuing the information at all, less your worldview is skewed by a faulty “ruler”.

Lastly, we should develop a bias towards skepticism and abstaining from judgment. The two best things you can do to avoid being duped, is to avoid unreliable information and withhold judgment when information is encountered. Simply abstain from accepting facts as true, unless you are willing to determine how they came to be.

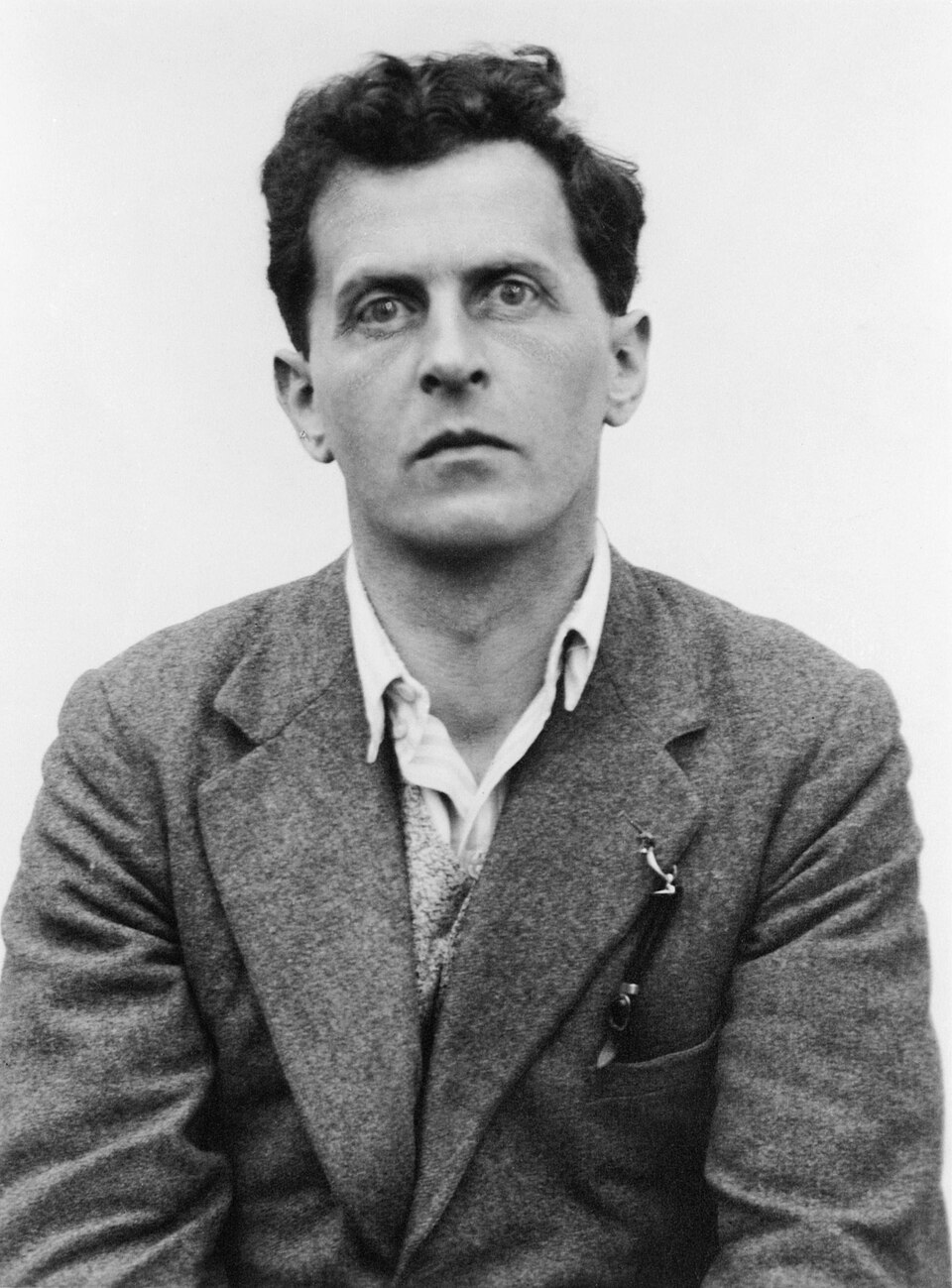

Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austro-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. This is a portrait for the conferment of the Trinity College scholarship 1929, taken sometime between 1928 and 1929.

In the case of the doctor’s visit and the fatal medical diagnoses at the beginning of this piece, your physician simply fell trap to naive empiricism. She exhibited the base rate fallacy, and with some basic understanding of Bayes Theorem, false positives and negatives, and a few repeated measurements, your physician could’ve determined that their original diagnosis was wrong.

Measurements and statistics promise certainty, but it is human beings that bear the burden of being wrong. If certainty carries authority, then error carries consequences, and the responsibility to reason carefully belongs not to our instruments and measurements, but to each of us.

Learn More

- Fooled by Randomness - Nassim Taleb

- Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Ludwig Wittgenstein