Self-Imposed Bounded Rationality

“Our ability to solve problems is limited by our conception of what is feasible.”

— Dr. Russell L. Ackoff

What is bounded rationality?

Bounded rationality is a concept that affects each of us every day. It refers to the idea that we are making satisfactory decisions with limited information instead of making the best decision with all the available information. Understanding this phenomenon can aid us in making better decisions.

Herbert Simon introduced the term “bounded rationality” as the replacement for “homo economicus” (or the economic man). The economic man is the portrayal of humans as agents that are perfectly rational, narrowly self-interested who make optimal decisions based on all available information.

For example, they assume that an individual looking to purchase a can of black beans knows all the available prices of black beans in the market and will choose the cheapest option, all else being equal. This would be the optimally rational choice. The problem with modeling humans in this manner is that it is completely divorced from reality. Most individuals have very little information, very little time to pursue information, and are not purely rational.

Let us assume you want to purchase a can of black beans. How long would it take you to get all the available information to make that decision? First, you would need the price of every single can of black beans on the planet. You would also need measures for the qualitative factors you care about. Things like taste, texture, the macronutrient content, amongst others. You would then need to consider changes to all this information over time. One black bean manufacturer might alter their process, a supply chain might shift, a farmer might purchase different machinery to grow the beans at scale.

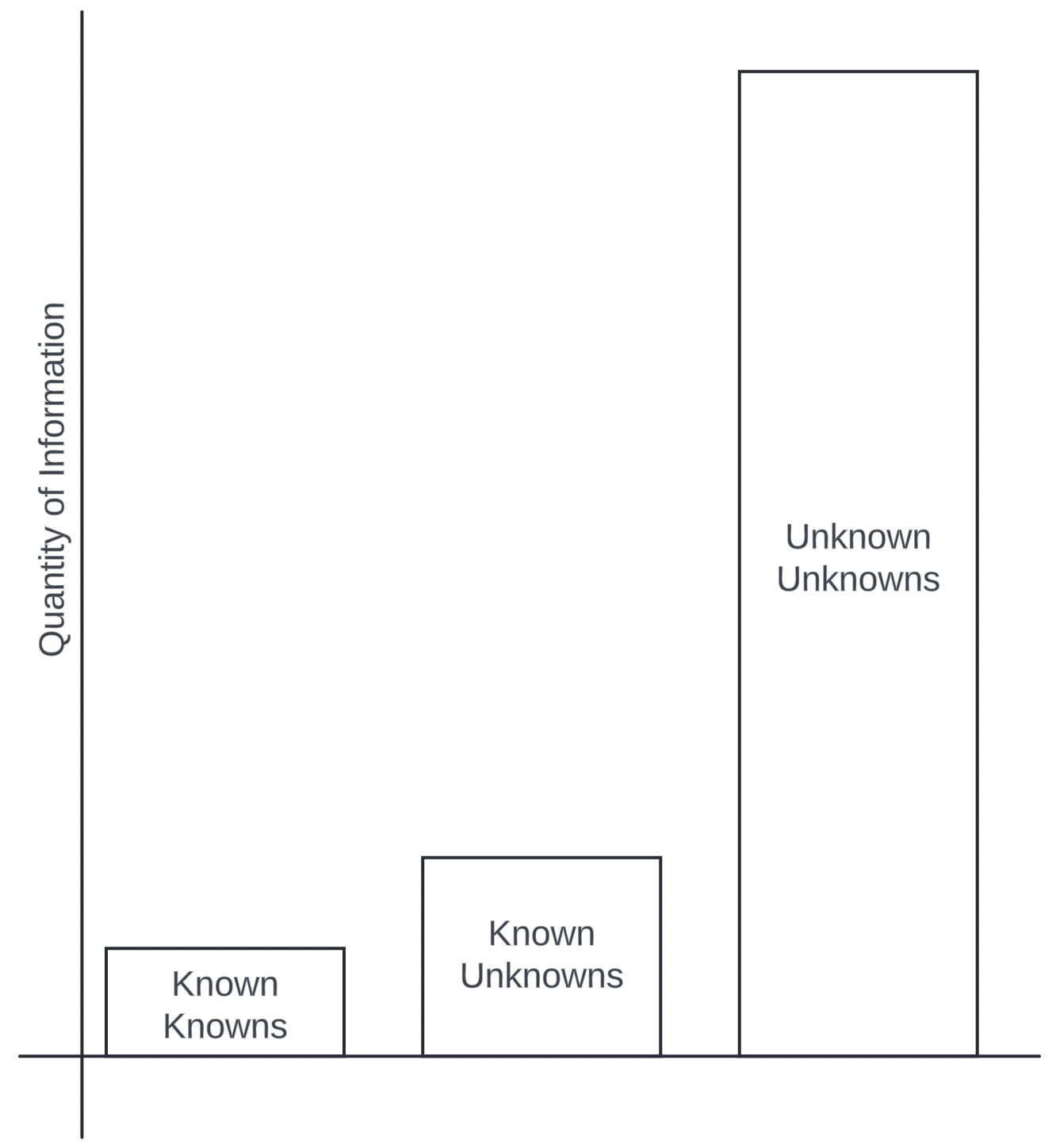

Most of the information in the world is unavailable to us. We are often overconfident and focus on what we conciously know (known knowns) and do not know (known unknowns).

Not only is our information imperfect but human beings are not rational either. Even when we believe we are being logical or rational, there is a large volume of work in behavioral economics establishing that we are far from it. We demonstrate a whole host of cognitive biases that cause us to deviate from rational behavior. For example, we tend to overestimate the likelihood of events that we can easily recall from memory. If I can easily recall the last time I witnessed a plane crash on the news, I am more likely to believe a plane crash could happen despite it being exceedingly rare.

The more you think through the assumptions associated with the economic man, the more untenable it becomes. Herbert Simon’s critiques and suggested shift towards bounded rationality make sense. Humans will never make decisions with all the available information and will always exhibit some form of irrationality and bias. Since we cannot escape this predicament, it is better to understand and embrace it.

Knowledge Thought Experiment

There is a phenomenal systems thinking speech on YouTube by Dr. Russell Ackoff. At one point during the speech, he explains the following phenomenon:

“There was an 83-year-old woman that organized different groups in her impoverished community. The area was poor and was missing simple functions like daycares, neonatal centers and other organizations. Eventually, the University of Pennsylvania opened a free clinic where local residents could get a checkup once a month. The woman left her most recent checkup and went home to her third story apartment. During her ascent up the stairs, she experienced a heart attack and died.”

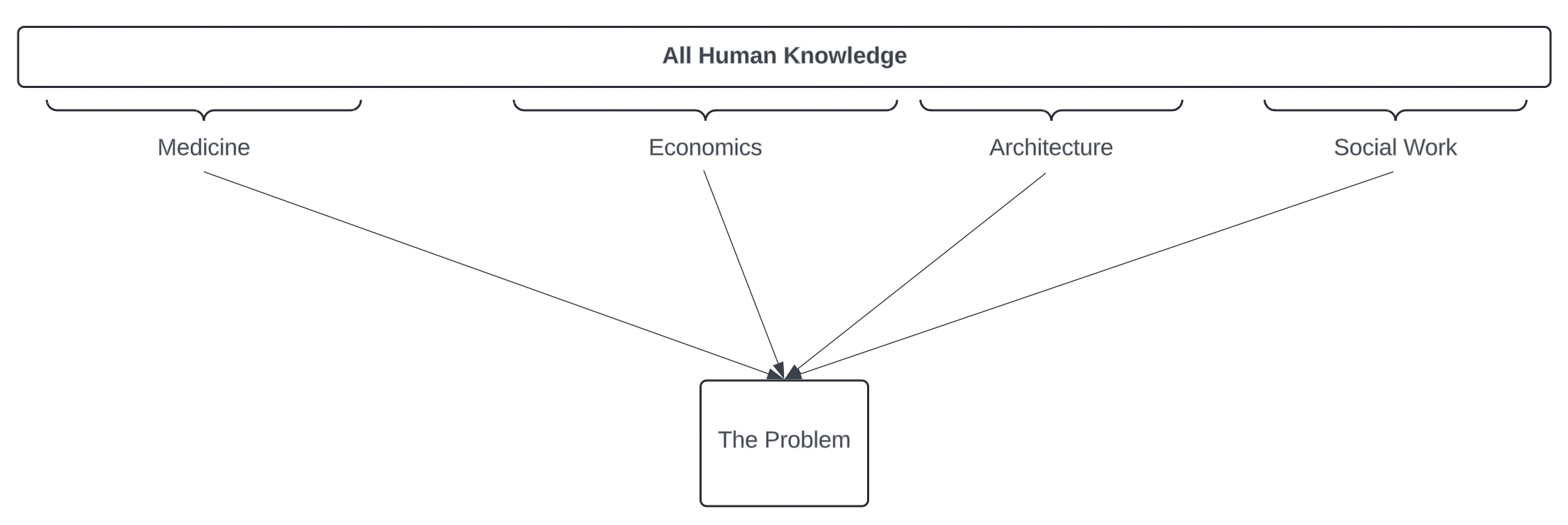

An interdisciplinary panel Dr. Ackoff was currently serving on responded with the following solutions:

- Professor of Community Medicine: This is a medical issue. We need more doctors.

- Professor of Economics: This is an economic issue. There are plenty of doctors, the problem is that they are private practitioners and too expensive. She couldn’t afford one.

- Professor of Architecture: This is an architectural problem. There should be elevators in those buildings.

- Professor of Social Work: This is a social issue. When she was young, she was deserted by her husband and raised her son who is now a rich and successful lawyer. If she wasn’t alienated from her son she could have lived in one of his many properties where she wouldn’t need to climb the stairs.

Dr. Ackoff then asks the following: What kind of problem is it? A medical problem, economics problem, architectural problem or social problem?

Before moving on, take a moment to come up with your own answer.

Knowledge as a Filing System

The answer is none of the above. It’s just a problem. Not an architectural problem, not an economics problem, just a problem.

Each adjective (medical, economics, architecture, social) describes the person proposing a solution and the subdomain of knowledge they want to draw on, not the problem itself. We organize knowledge into “knowledge domains”. Things like physics, machine learning, chemistry, political science, and music theory amongst others.

Many knowledge domains can contribute meaningfully to understanding and solving a given problem. Oftentimes more than one is applicable.

Dr. Ackoff tells us that we can think of these knowledge domains as a filing system for all knowledge. As an analogy, say you have a filing cabinet with customer information. Each file inside the cabinet contains a customer’s name, age, address and other demographics. You could organize the customers alphabetically or organize them based on location. The function of organizing them is to make it easier to locate the customers you care about but that doesn’t change the content of the files.

Like organizing customers alphabetically, knowledge domains tell us where to find specific knowledge. What they do not tell us is what knowledge to apply. It is fallacious and detrimental to our problem-solving capabilities to confuse “where the knowledge is” with “what knowledge do I need”. These are two very different things.

Self-Imposed Bounded Rationality

In school we teach people that a problem falls into one domain. We repetitively solve similar problems grouped by domains reinforcing this incorrect relationship (where is the knowledge vs. what knowledge do I need). You go to biology class, solve biology problems and repeat facts about biology. A bell rings and you go to economics class, solve economics problems and repeat facts about economics. Student’s intelligence is assessed via sanitized problems with a single correct answer that is right or wrong.

In the professional world we often hire for a narrow set of skills and job requirements, rejecting candidates that don’t meet the bar. Candidate’s relevance for their job is often determined by previous experience in a narrow domain (with a tool, a skillset, etc.) or education in a narrow domain (bachelor’s in marketing, finance, etc.). We regularly organize companies by functions (information technology, finance, etc.).

Our psychology also predisposes us to focusing on a single domain, often subconsciously and completely unknown to us. We are generally too confident in our judgements. We tend to favor information that confirms our current worldview, rather than new information. We favor people who are similar to us in appearance and ideology. We have a bias towards keeping things the same, rather than changing them. When others argue against or predispositions we tend to judge the arguments not on their structure, but on the argument’s conclusion. This is just a subset of the many ways the human mind entrenches itself and foregoes change for the current, familiar state. Even when that state is not the best one.

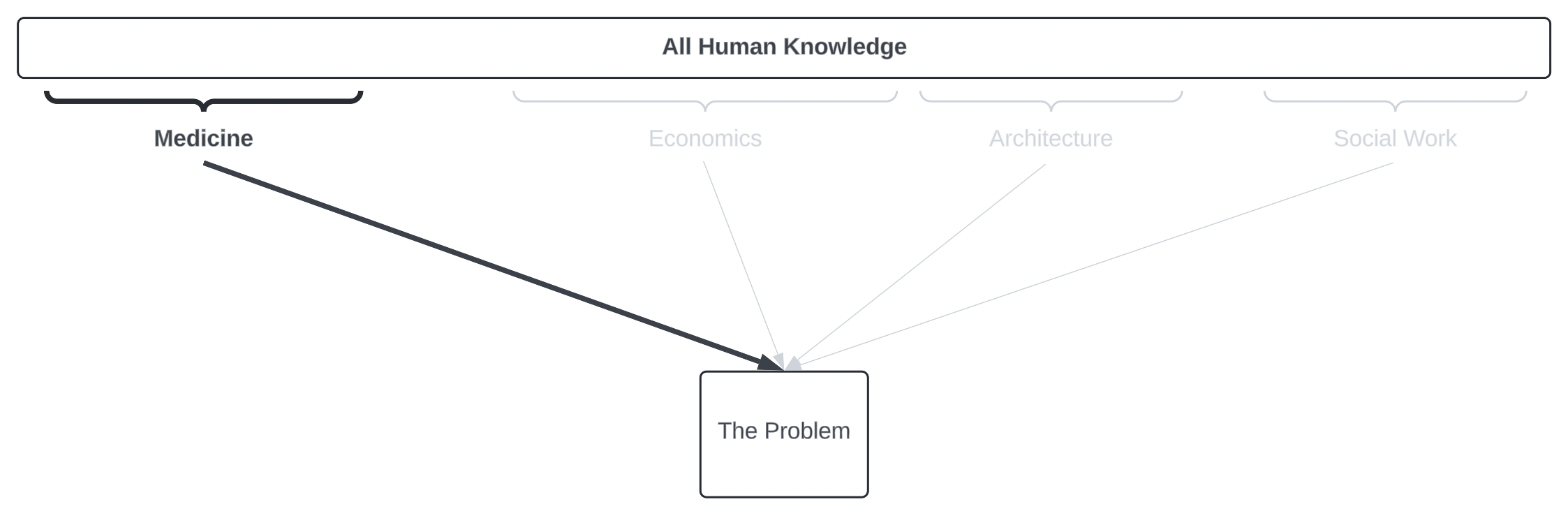

How a doctor views most problems throughout their day. Their job is to apply medical knowledge to patients, even when other domains of knowledge may benefit their patient’s outcomes. It is not entirely the doctor’s fault either. We respond to the systemic incentives of the environment we operate in.

I believe the combination of our learning institutions, organizations and psychological predispositions push us to bound our own cognitive toolsets into narrow subsets of knowledge. I call this “self-imposed bounded rationality”. It is our urge to stick to a narrow domain of knowledge when solving a problem.

People often willingly (or unconsciously) choose to neglect knowledge in another domain. Phrases like “this really isn’t my area of expertise” or “that’s something that accounting will need to take a look at” are indicative of this phenomenon.

| Mistake | Perceived Knowledge Domain(s) | Missing Knowledge Domain(s) |

|---|---|---|

| A doctor prescribes pain medication for back pain when a patient could switch to a standing desk instead | Medicine | Biomechanics, Kinesiology |

| A dietician prescribes a vegan diet to lower cholesterol when the high cholesterol is caused by exposure to black mold | Dietetics | Immunology |

| A physician overestimates a positive test result based on the prevalence of a disease and the test’s false positive rate | Medicine | Statistics, Probability |

| A social worker votes for a large government expansion of programs, not realizing the resulting deficit increase will cause the poorest in the population to lose purchasing power to inflation, effectively making them poorer | Social work, Sociology | Economics |

To be clear, I am not advocating that everyone be an expert in everything. As we discussed at the beginning of this piece, bounded rationality exists for us all. There are always constrains around the resources we can dedicate to learning and solving problems. That being said, we should also avoid consciously or unconsciously constraining our solution space. The world is only getting more complex. Innovative and novel solutions, by definition, come from new ways of thinking and integrating new knowledge.

Better Problem Solving

How does one avoid bounding their own thinking?

First and foremost, self-knowledge is critical. Understanding your identity can often elucidate biases. How do you or the teammate you’re working with describe themselves? Are they a doctor? A machine learning engineer? Identifying with problem solving, learning agility and delivering value to customers are timeless goals and always useful, no matter the domain. Spend at least some time honing these general skills, rather than learning specific ones.

Second, increase diversity of thought. The book “Range” by David Epstein has a plethora of examples outlining the benefits of cognitive diversity. One cannot know everything. Surrounding yourself with individuals with differing worldviews can provide a way to frame problems and solutions in a new light. Human beings are some of the most social creatures on the planet. Cultivating diversity of thought and collaboration broadens a group’s solution space and thinking.

Third, consider learning “laterally” rather than “vertically”. This advice was given to me by a great mentor early in my career. People often seek to move “up” in an organization. They work towards senior positions or management positions. In academia, we often pursue narrower, niche foci of research (Bachelors, then Masters, then PhD, then postdoc, etc.). Instead, consider moving to positions at the same “level”, especially early on in your career. For example, work as an entry level cybersecurity engineer, then an entry level graphic designer, then in operations and lastly as an entry level data analyst.

This helps you to quickly identify your strengths, weaknesses, likes and dislikes. Once you know what work you enjoy, and what you’re good at, then you can focus on sharpening those specific skillsets. People often spend the first half of their career on one track, only to realize their interests lie elsewhere.

This “lateral” learning approach is also beneficial because you can experience all the different types of work required to deliver a final product. It can help you understand where there is a lack of integration between groups. Consider someone working on a research and development team. They will perform better if they know what it takes to deliver and maintain a product in its end state because they can conduct their research with that final goal in mind. Generally speaking, humans work as a small part of a larger whole. The more knowledge you have about the overall objective, the more effective your individual contributions.

As a civilization we have come a long way. We’ve gone from sharing information around campfires, to sending information around the globe using pulses of light contained in deep sea fiber optic cables. We have the power to travel faster than the speed of sound, perform open heart surgery, genetically modify organisms for our benefit and surveil each other using satellites orbiting in space. The world we live in continues to increase in complexity. We cannot continue to progress as a species by bounding our thinking and applying the same, old solutions to solve new problems.

Some Personal Anecdotes

Some brief examples of self-imposed bounded rationality I’ve witnessed personally…

I worked at a manufacturing plant as an intern and watched a welder knowingly pass a defected part down an assembly line because he wasn’t responsible for quality control (there was a quality team at the end of the assembly process). The part was included in the final assembly of a grain bin. Three weeks later, two welders wasted six hours disassembling the exact same grain bin with a pair of plasma torches because it didn’t pass quality checks. This is bounded rationality by the welder.

A friend of mine who has struggled with asthma after living in an apartment full of black mold had to argue with her primary care provider that the prescribed albuterol inhaler wasn’t solving the root cause of her asthma (it was caused by mast cell activation from mycotoxins released by mold in her living space and body). The primary care provider explained that “the problem is with her lungs, so she needed to use the current medical protocol”. After charging insurance for a year’s worth of inhalers (and by proxy, increasing the cost of everyone’s insurance premiums) my friend saw a functional physician outside of her network who prescribed medications to remove the mycotoxins in her body and remediate the mast cell activation syndrome. This is bounded rationality by the primary care provider.

I witnessed a cyber defense team cause customers to lose access to their retirement portal for days because they deployed new firewalls across an organization without thinking to ask product teams how customers accessed their products over the internet. The cyber team had to spend a day remediating the issue, and then another week working with the product teams to determine the correct firewall rules to deploy. This is bounded rationality by the cyber defense team.

I saw a machine learning engineer train algorithms on computers ten times larger than they needed, just because they didn’t want to wait longer than a day to train the algorithm. This put a project over budget, overnight, because the engineer didn’t think about the costs associated with using a larger computer. This is bounded rationality by the machine learning engineer.

In all the above situations, simply consulting with others or slowing down to consider externalities could have remediated the problem. Instead, individuals put up their blinders and confidently charged ahead, thinking that their current information was sufficient.